Not So Gay at the YMCA

I said, young man, pick yourself off the ground.

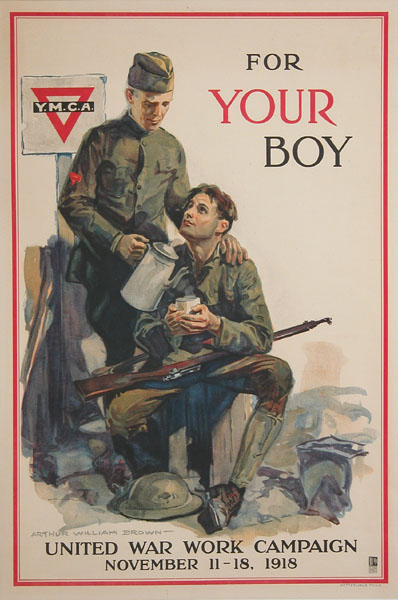

Near the entrance of the YMCA where I’ve worked out almost every day since 1996, there’s a vintage Y promotion from WW I posted above the towel bin. The image depicts two uniformed men together: one soldier, with gray hair and lines on his face, stands with a hand on the shoulder of the other, a seated youth bracing a rifle across his thighs. The standing man tilts a metal pot towards the cup in the hand of the other. Their eyes meet warmly. The motto at the top reads, “For your boy.”

As a straight woman, I appreciate the ironic poetry of these idyllic man-to-man images in California, a state where gay marriage rights have suffered a recent blow. I’ve seen a lot of men come and go at the Y, nameless regulars mostly, straight and gay and in-between. The thick-bodied black trainer with a head full of tiny braids. The Mediterranean seminarian in the long black cassock, who used to stride up to the check-in counter and gallantly drop his Adidas bag. In a wheelchair, the Philippino retiree who relearned how to move the left side of his body. The deaf man with red hair and weightlifting gloves, who showed me one day, kindly, how to adjust the seat height on the rowing machine.

But then there’s a guy I’ll call Ray: face raw red, dandruff goggles, wifebeater and pasty chest peeking from under the checkered shirt, yellow smile like always biting into what’s too big. Sixty-five, maybe seventy, wide shoulders sloped but still lumbering.

I try to avoid Ray. Or, I pretend to ignore Ray. But I always know when Ray is somewhere, there, perhaps at the dingy counter where the girl with a nose stud folds towels into rectangles and nods numbly at him. If Ray sees me exercising through the glass along the workout room, or through that glass and off a reflection in a mirror off another mirror, he pushes himself through the swinging door and heads my way.

At the squat machine, I’m glad for earbuds. He angles towards me slowly, like the zombies in bad old movies. As usual, I feign surprise and hard-of-hearing.

“Hey,” he says, as if this is the first time. “You still married?”

I hate this ritual. I dread how those teeth look so sore in his mouth. “Yup.” He’s already heard this. Then: “So: you soak in the tub today, Ray?” I mean the Jacuzzi in the men’s locker room.

“Me?” An arm swings out and his thick pink hand looks scrubbed and cold. “I tell you what--“ he jabs a thumb--“all I want is to take a dip without having to watch Phyllis and Martha in the water together.”

For whatever reason, I feel entitled to tease him. “Trying to get their hands on you back there?” I ask.

“Oh, I know there’s different kinds of people. Sure, I get that,” he says, looking towards the recumbent bikes no one is riding. “But some of these fags, they have agendas,” he says. “They’re just pushing and pushing it.”

The fag with an agenda. How many times have I heard that in my life? I press my feet into the platform of the squat machine, concentrating on numbers: 1,2,1,2. Most of the “fags” I know just want to be left alone. Vaguely, I hear Ray complain about a story he heard: some lesbian suing some doctor who refused--on religious grounds--to inseminate her artificially.

Then, abruptly: “You know what else I don’t get? These people who have sex with little kids.” He forces a laugh, a kind of huff that lifts his shoulders. His index finger points: the locker room again, the Jacuzzi. “Back there’s the only place I feel really naked.”

I adjust an earbud and give him a look like, “Who knew?” I’m done now. Ray skulks out the back, past the treadmills and the Bowflex, fading into a pale, hunched square in the mirror.

During the past thirteen years, I’ve seen Ray hand over his laminated photo card, harass the staff in his awkward but deliberate way, take a towel, and head for that locker room hundreds of times. I’ve observed that’s he’s fairly devout about the hour, somewhere between 10:30 a.m. and 1:00 p.m. each day.

I’ve never seen Ray on the treadmill, or with the free weights, or at the exercise machines. But every day, he does push himself through the locker room door, into the place he has just told me that he feels “really naked.” He must sit in there, or wait there--on a bench or plastic chair, fully clothed or in his bathing trunks or underwear, paging through the newspaper until the smudge comes off on his hands. Maybe he decides, finally, why not take a shower? He washes himself when other men are there, pretends to ignore them, maybe tells a dirty joke or says something about “immigrants” or “gays” so loud that in the cement-floored communal stall he can barely hear the tight spray falling.

What worries Ray most--the penises? the flab? Worse, maybe: young muscle or thick hair glistening with trails of water? His own mottled pinkness under the light?

It could be a vague recollection: of touching, or getting touched. Of not touching, but wanting to. Of hurting someone?

Am I intruding, to wonder--since, after all, Ray’s got men on his mind? As I push my toes against the edge of the platform for a final set, I think of how my calves will never be defined like my husband’s. But I can easily talk about touching his legs: the wiry hairs along the hard shin, the taut harp of muscle underneath. On one leg, the smudged pink birthmarks that look like fingerprints. I can write this now, and no one will ask me about my agenda.

I wonder if I’ve seen or spoken to the guys Ray calls “Phyllis” and “Martha.” There’s a new young guy who gives massages here. He has coppery skin and flirty, dark lashes at the edges of his doe-eyes, and when I see him, he always gives a childlike wave with a lithe arm. Some days he wears a YMCA shirt with a bright rainbow across the front.

I picture Ray tucking a towel around himself after taking a sauna or padding out of the shower, fabric folded up under his soft armpits, like a modest courtesan, his voice grating above the slap of someone’s flip-flops: “When I was in Nam….”

Finishing at the squat machine, I hear George Michael blast in my earbuds: Freedom. Hold onto my freedom. That wouldn’t be the song in Ray’s ear. Not the Village People, either. Something more antique, more melancholy, probably in another language. “Real music,” Ray might say. “Not like they have now.” Say, “O Mio Babbino Caro” from Gianni Schicchi. Or The Andrews Sisters, “Bei Mir Bist due Schoen.”

Near the swinging door someone weeks-ago attached a bottle of hand sanitizer for patrons on our way in and out. It is part of my closing ritual now, though what could it bless? I pump a blossom of white foam into my palm, rub and rub until it sinks into the skin, leaving clean spaces between each finger.

I feel something new, something weird, as I collect my keys and toss my towel in the bin and head out to the parking lot, to my car, the drive home to my husband. For all these years I have despised seeing Ray, but for the rest of this afternoon I’m sorry, though it may not be my place: I’m sorry for the men who still can’t look at each other, and who, gay or not, still have a need to feel down--even here, and even now. At the Y. For your boy.

Jo Scott-Coe's work has appeared in many publications, most recently Hotel Amerika, turnrow, Green Mountains Review, River Teeth, Memoir(and), Ruminate, and the anthology (Re)Interpretations: The Shapes of Justice in Women's Experience (Cambridge Scholars Press). Her interviews with essayist Richard Rodriguez and poet Donna Hilbert have been featured in Narrative and Chiron Review, respectively, and she received a Pushcart Special Mention in nonfiction for 2009. In November 2009, Scott-Coe will present research on gender and violence in education at the National Women's Studies Association "Difficult Dialogues" conference in Atlanta. She now works as a new assistant professor of English composition and creative writing at Riverside Community College in Southern California.

Jo Scott-Coe's work has appeared in many publications, most recently Hotel Amerika, turnrow, Green Mountains Review, River Teeth, Memoir(and), Ruminate, and the anthology (Re)Interpretations: The Shapes of Justice in Women's Experience (Cambridge Scholars Press). Her interviews with essayist Richard Rodriguez and poet Donna Hilbert have been featured in Narrative and Chiron Review, respectively, and she received a Pushcart Special Mention in nonfiction for 2009. In November 2009, Scott-Coe will present research on gender and violence in education at the National Women's Studies Association "Difficult Dialogues" conference in Atlanta. She now works as a new assistant professor of English composition and creative writing at Riverside Community College in Southern California.