Let’s Run Away and Join Jason Bredle’s Carnival: A Review by Isiah Fish

________________________________________________________________________________________

<BACK TO TOC |

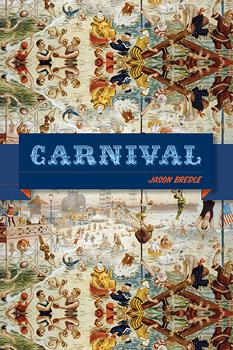

Carnival

Jason Bredle

Akron Series in Poetry

August 7, 2012

85 Pages

ISBN 13: 978-1937378189

$14.95

I’ve been meaning to get on my knees and thank the stars for leading me to the Amazon page where Carnival sat waiting in the recommended section next to Jason Bredle’s other masterpieces—Standing in Line for the Beast and Smiles of the Unstoppable. I ordered it without a thought and when it arrived wrapped in the pungent smell of cardboard and delivery-man hands, I sliced it open carefully, the way an intelligence agent opens a package that’s potentially a bomb.

You don’t read a poetry book from cover to cover, especially one written by Jason Bredle, whose boundlessly imaginative prose tends to crack the glass on a weird-o-meter. Instead, you slide your finger up the middle of the pages like a horny teenage boy on his first trip past the undergarments, penetrating it, then ripping it open to see what the eye can make love to.

After elevating Smiles of the Unstoppable to my own personal poetic Bible, I had high hopes for what would soon become my inspiration-prescription, and as I stroked Carnival, the laughs rose and the euphoric feeling of inspiration washed over me as if a muse was massaging my earlobes.

In sixty pages of half-page hilarious prose poems, Bredle defamiliarizes everyday thoughts by twisting them until they burst with confetti and the unknown, then, usually at the end of the poem, he remembers to ground it in pathos usually in the form of an ending line that leaves you breathless, and makes you exist in a new way.

This phenomenon rings truest in “The Proselytizer,” a poem half-way through the book that takes you on a train of thought beginning with a relatable human statement: “Emotionally speaking, I’m a mess.” The poem then references Richard Dawkins and how the man creeps the narrator out. After this we are taken on a philosophical journey exploring time and space, the idea of a supernatural creator, before ending with “Look at the sky. We’re someone else’s heaven.” These ending lines bring the thought-train to fruition, posing a fierce and unbelievable question while simultaneously carrying extreme poetic magnitude: Are we alone out there? What does it all mean? The idea of being heaven gives rise to one’s own thoughts on the matter: is Earth where people come when they die somewhere else? If so, our heaven could be another planet. This is a fantastic way to broaden one’s own horizons and potentially write their own poems about the subject.

Something interesting that Bredle does is introduce us (without introductions) to characters by throwing in proper nouns and expecting us to get acquainted to them without exposition. We meet Pablo on page twenty-five, and he goes through the looking glass. We meet Giancarlo on page thirty-three, and he makes the narrator wear a sexual fantasy and walk from one end of the city to the other. We stay with Giancarlo as he invites the narrator to a party and gifts him with vibrating underpants. We meet Trevor and Carol but never stray too far from Giancarlo and his well-endowed penis. Bredle’s quirky way of acquainting us with these characters is ultimately a device that draws us closer to the poems. It’s as if the poems are extending their hands and shaking ours, and this allows readers to form a friendship with the unorthodox characters as if they are right alongside them.

Similar to the proper-name feature, Bredle continues his pop-culture references in this collection as well. Like in his book Pain Fantasy, where he was joined by, he teams up with Jim J. Bullock, Shadoe Stevens, and Alf to win an electric guitar. We also encounter Rimbaud, The Outsiders, Ja Rule, and Thomas C. Howell.

Bredle is a master at movement. His poems do not stay in the same place, but flow like a twinkling stream at dawn, seamlessly bending over immobile rocks and dancing until they reach a river. In “Zion,” the narrator begins by introducing a question, “What is it, overall, that you’re kind of looking for?” and then jumps to “The neighbor’s cat and I are on the run,” and as the poem progresses, Bredle finds ways to seamlessly transition in a way that doesn’t disrupt the flow or pull the reader out of the poem. This is especially true in the ending lines:

You write a letter to your family. You fold the letter into a baby’s shoe. You leave the shoe in a field of wildflowers. I’ve seen the cat chase and eat a dragonfly. I don’t want to live. I wish I were dead. I’ve said the words so many times they don’t mean anything anymore.

With these lines you can see the movement. The letter is written, then folded into a shoe, which is left in a field, then back to the cat, then a statement invoking pathos, and an ending that grounds it all.

Besides his rants on the pressure of nailing down the first eight sentences in a poem (“Cophenhagen Airport”), and discussing how Giancarlo’s shenanigans got him bitten by a miniature horse again (“The Tiger”), Bredle has some powerful yet muted things to say about love. Overt love poems are one of the seven deadly sins due to the fact that it’s all been said and done. So Jason Bredle sneaks in the love with surreal and fresh lines: “If I could, I’d tattoo your name on my skeleton.” Then, he turns down the whacky and soothes us with a line that’s so simple it’s endearing and affectionate: “Will you do one thing for me tonight? Will you put on your favorite dress and sit with me?”

After Carnival, perhaps you won’t know what to do. It tends to make you want to scream under a busted fire hydrant or stroke a cat and sip warm tea, and maybe the tea bags will have faces, and maybe the cat will cry. Perhaps you’ll be inspired enough to write, or to think about things you never thought much about until you start creating your own theories.

One thing is for sure: Bredle is giving us growth with Carnival. In Standing in Line for the Beast he showed us he can stretch a poem for pages and not fall short or lose the humor. In Pain Fantasy he gave us stanzas and by far the most random juxtapositions we’ve yet seen. In Smiles of the Unstoppable he reigned in the arbitrary craziness and strived more a more fluid, refined kind of crazy. Now, with Carnival, he has taken on the prose poem. He’s polished and condensed them, showing readers a new range and touching them with poems that are one paragraph each. Carnival certainly poises Bredle’s future for the arrival of more hilarious books. It’s uncertain what journey he will take readers on next, but whatever it is, there will most likely be a cat and a miniature-horse riding guy named Giancarlo involved.

_________________________________________________________________________________________

Isiah Fish is a junior Creative Writing major at Western Kentucky University. Writer of poetry and fiction, he’s won the Flo Gault Student Poetry Prize, WKU’s Gender and Women’s Studies Writing Contest, and the Goldenrod Poetry Festival. His work was featured in the 2013 Albion Review.